Friends, Comfort, and the Big Terrible After

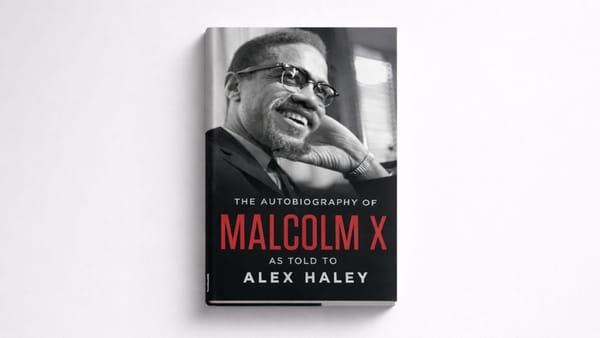

Chandler was my favourite because he felt exposed. Reading Matthew Perry’s memoir made me realise why the joke always came first.

I grew up with Friends. It wasn’t something I discovered on my own. My sister introduced me to it, casually, the way people introduce you to things they don’t realise will end up stitching themselves into your life. At first, it was just a show. Then it became a habit. Then, slowly, it became comfort.

I watched it when I was sick, curled up and half-conscious. I watched it while eating alone. I watched it when I was bed-rotting, when the day felt too long and I just needed something familiar to keep me company. I watched it to pass time, and sometimes to avoid thinking. At some point, it stopped being background noise and started feeling like a place I could return to. I know almost all the lines. Not because I tried to memorise them, but because repetition does that when something matters to you.

Chandler was always my favourite. Not because he was the funniest, well he was, but he was my favourite because he felt the most exposed. The awkward one. The guy who makes the joke first, especially at his own expense, so no one else gets there before him. The guy who uses humour as armour. I see myself in him more than I’m entirely comfortable admitting.

That’s probably why Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing hit as hard as it did.

Matthew Perry opens the book with Pain, capital P Pain, and it’s not theatrical. It’s precise. The kind of pain that strips language down to its barest function. As the memoir unfolds, it becomes clear that the wit, the timing, the Chandler-ness of him wasn’t just a talent. It was survival. A way to stay visible without being known too well. A way to be loved without risking abandonment.

When Perry writes, “If I drop my game, my Chandler, and show you who I really am, you might notice me, but worse, you might notice me and leave me,” it feels less like a confession and more like an unmasking. It’s the fear underneath the joke. The reason the joke exists at all.

There’s a line in the book that says, “Knowledge avails you nothing,” and it stuck with me because it’s brutal in its honesty. Knowing what’s wrong doesn’t mean you can stop it. Knowing better doesn’t mean you’ll do better. Addiction, loneliness, self-sabotage, they don’t care how smart or self-aware you are. They move anyway.

Perry writes openly about fame, about addiction, about relationships that collapse under the weight of his own unhealed parts. He admits, without softening it, that at forty-nine he was still afraid to be alone. That fear feels embarrassingly familiar. The fear of silence. The fear that without noise, without performance, there’s nothing solid left.

When I first read this book, he was still alive. That matters. I read it thinking of it as a survival story. A painful one, but one that had landed on the right side of the sentence.

Then he died.

And now I can’t bring myself to watch Friends. I haven’t been able to since. Something about it feels altered, like the safety net I didn’t know I was leaning on suddenly disappeared.

It hurts in a way I didn’t expect. Not because I knew him, I think it was because he was present in my life in this strange, one-sided, deeply intimate way. Because a character he created helped carry me through moments when I didn’t have much else. Because reading his words now feels like hearing someone explain the joke after you’ve already laughed for years.

This book isn’t just a memoir. It’s a reminder that there is a hell, and that it often lives inside us. That people we think are doing fine are sometimes just very good at hiding. And that humour can be both a gift and a wound.

For me, reading this book felt like looking into a mirror I hadn’t planned to stand in front of. It reflected fears I recognise. The impulse to deflect. The exhaustion of being “on.” The longing to be loved without having to perform for it.

Perry ends by saying there is light in the darkness, if you look hard enough. I believe he believed that. I believe it too. But right now, the loss still stings. The show still sits untouched. And the book remains a reminder that sometimes the people who make us laugh the hardest are carrying things we never fully see.

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe that’s the terrible thing. And maybe, somehow, sitting with that truth is part of learning how to live with our own.